Thank you to Ray Robinson and Jeff White for sharing this week's interesting feature on the LORAN system.

LORAN

Jeff: Back in March, we received an email from Wavescan listener Fred Waterer who forwarded an article by Eric Blunt in Port Weller, Ontario, Canada about a Mrs. Marian McKnight who had just celebrated her 100th birthday, and who had served as a WREN in World War II at a remote top secret LORAN base on the coast of Nova Scotia. Not familiar with LORAN? Ray Robinson in Los Angeles has been finding out more.

Ray: Thanks, Jeff.

|

| LORAN/Wikipedia |

So first, what was LORAN? Well, it stood for Long Range Navigation, and was a top-secret system developed in the United States, which allowed ships and aircraft to pinpoint their positions at ranges of up to 1,500 miles, or 2,400 km, from land. It was first used for ship convoys crossing the North Atlantic, and then by long-range patrol aircraft, but it was also eventually used extensively by ships and aircraft operating in the Pacific theater during World War II.

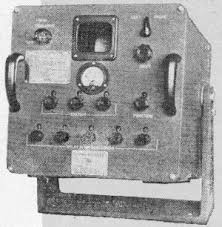

The concept of the system was to allow a vessel or aircraft to determine its position in all weathers and at great distances from shore. A radio wave is sent from a master station and is received both by the ship or plane and by a slave station on a different part of the coast. On receipt of the pulse, the slave station then sends out another pulse, which is also received by the vessel or plane. The LORAN receiver on the ship or plane measures electronically the difference in time of arrival of the radio waves from the ground stations, and then using LORAN charts for the area served by the ground stations, a line of position can be determined from the time difference. A second line of position is determined from another pair of stations. The intersection of the two lines provides a fix. The system also allowed the ships and aircraft using it to maintain radio silence.

The original system, also known as LORAN-A, used two frequencies in the Marine Band, above the AM Broadcast Band, at 1850 and 1950 kHz. These frequencies were also within the Amateur 160 metre band, and amateur operators were under strict rules to operate at reduced power levels to avoid interference, especially near the North American seaboards. Depending on their location and distance to the shore, U.S. operators were limited to maximums of 200 to 500 watts during the day and 50 to 200 watts at night.

Because of this choice of frequencies, signals could be reflected by the ionosphere at night, and thus provide over-the-horizon operation.

Originally developed by the MIT Radiation Laboratory in Cambridge, Massachusetts for the United States Navy, in mid-1942 the project was also joined by the U.S. Coast Guard and the Royal Canadian Navy. The Canadian liaison was required, because the ideal siting for the land-based stations to cover shipping and aircraft in the North Atlantic was along the coasts of the Canadian Maritime Provinces.

|

| LORAN/Wikipedia |

One site in Nova Scotia proved to be a battle; the site was owned by a fisherman whose domineering teetotaler wife was dead set against having anything to do with the sinful Navy men. When the site selection committee was discussing the matter with the husband, a third visitor arrived and he offered the men cigarettes. They refused, and the hostess then asked if they drank. When they said they did not, the land was quickly secured!

The first locations went live in June 1942 at Montauk Point, New York and Fenwick Island, Delaware, but they were soon joined by two stations in Newfoundland at Bonavista and Battle Harbour, and then by two more stations in Nova Scotia at Baccaro and Deming Island.

Additional stations all along the U.S. and Canadian east coast were installed through October, and the system was declared fully operational on January 1, 1943, at which time, authority over the system was transferred from MIT to the U.S. Navy. Two more frequencies were brought into use, at 1750 and 1900 kHz. By the end of 1943 additional stations had been installed in Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands and the Hebrides, offering continuous coverage across the North Atlantic.

So now we come to the article by Eric Blunt, forwarded to us by Fred Waterer. Eric wrote:

“Mrs McKnight is 100 years old today (that was on March 11, 2025). Some people we know may have had experiences we had no way of ever imagining. I knew she was in the WRENs. She never hid that and was very proud of it. But the details she never shared. Of course she was sworn to secrecy under the Official Secrets Act. While never enforced, the penalty for treason for most of her life was death. So her reticence is understandable. I knew her as a sweet and caring kindergarten teacher. Who knew she was also a badass explosives trained soldier!

Growing up, Marian McKnight was fascinated by stories of the sea. When the Women's Royal Canadian Naval Service, nicknamed the WRENs, opened in 1942, Marian knew this was her calling. Her family and boyfriend thought otherwise, actively discouraging her. But this negativity culminated in her going on to become the first girl from her graduating class to enlist in the military, and her determination was likely a deciding factor in her being selected to serve at an extremely remote station in Baccaro, Nova Scotia. Taking an oath of secrecy and undergoing a thorough background check, she was among 16 women responsible for maintaining the top secret LORAN system at that location.

Maintaining the LORAN transmitter was not easy. Working in shifts of four, the WRENs had to ensure that their signal was synchronized with two other LORAN stations, one Canadian and one American. Marian told me the frustration of when the LORAN system went out of sync and the scramble to fix it, leaving any ship or plane using it in the dark as precious seconds ticked away. This had to be kept running 24 hours a day.

One night two German U-boats were detected half a mile from their station. It was a tense 48 hours before the two U-boats slipped away. If the U-boats had landed, the women were instructed to detonate explosives underneath their machines “and run like hell.” The women were also armed, but were terrified to use the supplied rifles. Under no circumstances could the LORAN system fall into enemy hands. The WRENs of Baccaro hold the unusual distinction of being the women closest to enemy forces on Canadian soil during the war.

Recently the British government awarded Marian the Bletchley Park Commemorative Badge, given to veterans who served at top secret stations across Britain and Canada.

Thanks, Fred, for forwarding that very interesting article

Marian McKnight is holding the Bletchley Park Commemorative Badge, which was awarded to her by the British Government.

The enormous

distances and lack of useful navigation points in the Pacific Ocean led to

widespread use of LORAN for both ships and aircraft during the Pacific War. In particular, the accuracy offered by LORAN

allowed aircraft to reduce the amount of extra fuel they would otherwise have

to carry to ensure they could find their base after a long mission. This reduced fuel load allowed the bombload to

be increased. By the end of World War II

there were 72 LORAN stations, with over 75,000 receivers in use.

Back to you, Jeff.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)